Rules for Fair Digital Campaigning

Policy Brief

Election campaigns and other political campaigns have long moved from the street to the web. Online, political parties and other political organizations reach many people at once using their own channels in social networks, their own apps and messenger groups as well as advertising and influencers. This trend has not only been visible in the US, the UK and France for years, but is seen in Germany as well: German political parties alone paid an estimated 1.5 million euros for roughly 80,000 ads on Facebook and Google in the wake of the 2019 European Parliament elections, which were seen millions of times. Political parties, but also other political advertisers, can use ads on social networks to present their positions, criticize their opponents, recruit volunteers and drive donations.

Political advertising happens under different circumstances online than offline

This online political campaigning, in part fueled by targeted ads on social media, is based on different foundations than traditional political advertising on TV and on the street. Paid political communication online is data-driven, personalized and happens on digital ad platforms. Based on personal behavioral data collected on the web and on mobile devices, ad platforms create profiles of voters. Political parties and other organizations can use this breadth of data, which is not available offline, to target groups according to certain (assumed) preferences and dislikes. The breadth and depth of behavioral data also helps platforms’ algorithms show political messages to exactly those people who are most likely to interact with them. Apart from that, political campaigns can more easily and more often test how their messages work among what populations – often without users knowing about this. None of this is possible in the same way with poster campaigns, postal mailings and personal voter outreach on the street.

Risks of political online advertising: Distorted debates, big-money interference and lack of public interest scrutiny

It is a positive and necessary development that German political parties and campaigns try to reach voters and supporters on the web. Yet, the rise of political online advertising also comes with potential risks for individuals and society. Firstly, political online advertising in its current form can harden societal tensions: Narrowly targeted advertising, aimed at homogeneous groups, can lead to people only receiving messages that reinforce their own views and their fears of the other side. For these are likely the ads that users will “like” and share. Secondly, well-financed interests can flood the online information environment with their ads and can thus drown out other political opinions. Thirdly, online political advertising remains opaque despite some transparency measures. The high number of ads and their algorithmic delivery make counter speech and public interest scrutiny, as the media and citizens do for traditional ads, hardly possible. This opens the door for potential discrimination and negative campaigning, which remains unseen and unopposed.

Existing rules and laws are outdated and are barely able to address potential negative effects of digital campaigning

Germany is ill-equipped to deal with the technological changes and the associated potential risks seen in online political advertising. Existing rules and laws for political advertising were developed for the offline sphere and can barely offer protection anymore. For example, there are clear rules for postal mailings as to what demographic data may be used by whom for that. For behavioral microtargeting online, it is mostly platforms themselves deciding how targeting works. The European General Data Protection Regulation can at times limit microtargeting but has weaknesses in other parts regarding profiling. Broadcasting regulation in Germany ensures that even rich advertisers cannot flood the airwaves. Similar restrictions could be part of the newly created Interstate Media Treaty, which remains vague on this, though. Voluntary, self-regulatory measures exhibit serious flaws, too: To enable at least a little bit of public interest scrutiny and partly under pressure from the EU, platforms have developed political ad archives. These databases collecting political advertising are meant to allow an analysis of what political groups target voters with what messages. However, the archives are error-prone and offer citizens and researchers only rudimentary information. Transparency reporting obligations for political parties are rudimentary, too, revealing little information on ad spending.

What rules on online political ads are necessary in Germany and the EU

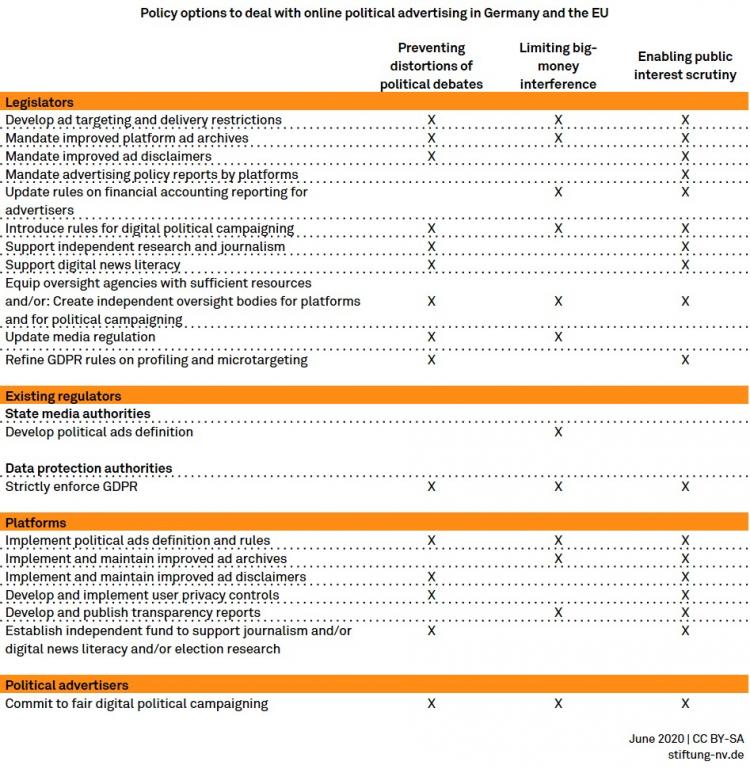

The lack of clear guidelines for paid political communication online is a danger for free, open, pluralistic political debates. Election campaigns in the US, the UK and many other countries have shown this over the past couple of years. Even though Germany has a different political system and a different political culture, lawmakers in Germany should be active in finding ways to address these risks that exist in this country as well. Therefore, rules on political advertising should be updated and expanded. The following measures should be discussed to safeguard elections and political debates.

Restrictions on behavioral microtargeting

The most urgent task is to prevent online political advertising from being tailored very narrowly to the (assumed) identity traits of voters and from mostly trying to strengthen their existing positions and fears. To that end, legislators should set clear limits for political microtargeting. Targeting and delivering political ads should only be allowed using some limited demographic data, and it should be prohibited to use comprehensive personal, also inferred, behavioral data for this. Voluntary microtargeting restrictions by some companies have to be expanded and made mandatory across platforms. A minimum size for target groups could also help in making political advertisers address bigger, more heterogeneous groups and not narrowly target citizens’ preferences and fears, which might heighten polarization. This could also be achieved with financial incentives, such as discounts for large, heterogeneous target groups. Moreover, users should have better ways to decide for themselves if and how they see political advertising.

A sort of quota for political online ads, as seen in broadcasting regulation, could be one way to prevent user feeds being flooded with ads. But it would have to be completely revamped for the online space and have different criteria than offline. For that to work, an updated definition of political advertising is necessary, which acknowledges the specific characteristics of the online sphere. Tiered spending caps could also be discussed as potential solutions.

Expanded campaign finance oversight

Campaign finance oversight in general should be expanded, so that not only political parties are covered, but also paid communication of other political movements and organizations. There should be verification mechanisms for political advertisers that do not rely solely on the platforms’ definitions. Financial reports should be enhanced as well to provide more details on digital ad spending, among other things.

Transparency obligations for platforms

There should be certain transparency and accountability requirements for platforms to allow public interest scrutiny of political online advertising. This should include mandatory ad archives with standards for expanded, detailed information on ad targeting and ad delivery criteria. Transparency reporting on platforms’ ad practices should be required. While many companies already have policies on ad content, less is known about the way targeting and algorithmic ad delivery works. Expanded mandatory reporting could make it easier for external observers to check corporate policies against actual ad practices. Subsequently, tech companies could be urged to allow independent auditing of their ad algorithms.

Independent body to check transparency obligations

The lack of transparency and accountability requirements reveal how little oversight there is for large platforms’ data-driven, algorithmic ad business model. Germany should advocate at the European level to change this. Oversight mechanisms will be part of the discussions for the Digital Services Act, for example. This would be a suitable place to codify things like industry-wide reporting requirements. Such oversight mechanisms should acknowledge differences in size and market power between platforms. It should also be clearly spelled out who transparency measures are supposed to be for, what they are supposed to achieve and who is supposed to check them. For example, ad archives are not only helpful for users themselves, but especially for researchers and independent oversight bodies, and should thus take into account their needs as well. If this enables studies to help improve understanding of political advertising, citizens benefit indirectly. Ad disclaimers in users’ feeds benefit users directly and should be designed in a way that users have options to take action on how political ads are displayed to them. External checks of these transparency guidelines and measures are necessary. For that, it is important to ensure that the oversight body is legitimized by parliaments, independent from government and industry, and equipped with expertise, budgetary resources and sanctioning powers. The discussions on industry oversight should ideally be held at the EU level as well.

More and more, election campaigns and political movements are built online. Political parties and other political advertisers already spend millions on ads on social media, video portals and search engines. These large digital ad platforms offer different opportunities for paid political communication than offline. It should be elected officials who determine rules for this and not private companies.

Dr. Julian Jaursch